Sourcing World-Class Statements Of Work

- MMGMC

- Nov 19, 2022

- 13 min read

Updated: Nov 20, 2022

Vast sums of money are spent every year on IT consulting, legal, management consulting, engineering consulting, and other complex services performed by highly skilled people. We estimate that the global annual spend is around $500 BN with the US accounting for 75% of the total. These projects are typically governed by Statements of Work (SOWs) that spell out what the contractor is supposed to do, how long it will take, and what it should cost.

Our analysis of SOWs shows that 75% are poorly structured, providing little managerial control, transparency, or incentives for vendors to perform. Best-in-class SOWs provide about 35% lower project cost and take half the time to complete when compared to typical SOWs.

Much has been written about how to manage SOW projects, but not enough attention has been paid to strategically sourcing SOWs. This paper will lay out a practical approach to sourcing world-class SOWs for successful project outcomes at reduced cost and more manageable risk.

Global SOW Expenses

While statistics are difficult to come by, we estimate that corporations, governments, and other institutions worldwide spend up to half a trillion dollars on SOW-intermediated human labor. The majority of this spend is driven by IT consulting and engineering, with legal, consulting advertising, and other services accounting for the remainder. SOW spend is often grouped with contingent labor, but this classification ignores the much higher skill requirements, the strategic importance of SOW projects, and the unique management techniques required.

Worldwide Contingent Labor By Work Arrangement

In $T

What makes SOW labor different?

Complex projects designed to create custom products that coordinate multiple parties are not fundamentally novel. Building construction for example is a very mature case, where many specialties like architects, planners, contractors, completion bonds, etc. have evolved to address the issue. In contrast, IT, engineering, management consulting, and creative services are more recent phenomena that are less precisely specified, harder to check and approve, and with fewer options to switch providers in the middle of a project. The key characteristics that make SOW sourcing so difficult are:

In many ways, SOW projects are more like marriages than commercial contracts, involving a lot of pain and few options should things go wrong. The reality is that the buyer purchases an expensive custom product with hard-to-assess specifications and few if any switching options once substantial work has begun. SOW contracts tend to be priced between a true service product and marked-up contingent labor. The very existence of the SOW project implies that the vendor is somehow able to achieve higher productivity than the buyer could achieve by coordinating the work of similar resources themselves. In other words, the vendor provides productivity-enhancing technology with significant implicit value in addition to resources.

Contingent Labor Classification Framework

Characteristics of effective SOWs

Based on our extensive management consulting experience, we believe that effective SOWs exhibit five key characteristics, which we will examine in detail:

Transparency. The SOW should contain clearly defined economic terms including prices, that are directly attributable to the economic value of the service being provided. We often find that SOWs are long on legal language but short on relevant economic terms, which leaves managers with a poor understanding of the project economics and how to intervene. A good litmus test would be to check if one could mathematically match a bottom-up calculation to the stated top-down contact, e.g. by adding up per diems for resources and timelines and matching them to projected deliverables. Another test is whether the A/P system can match payments to vendors to SOWs or sub-sections thereof. Lack of transparency indicates savings potential.

Competitiveness. Within the existing pricing framework, which almost always includes resources and projected hours, a competitive SOW should be in line with best-in-class metrics for per diems, hours consumed, and job specifications. One should ask the following questions in sequence:

Right price: What if I substituted the SOW per diems with competitive benchmarks?

Right location: What if I selected an optimal location for each resource?

Right Skills: What if I matched the job requirements of the SOW to the right resources?

Right Quantity: What if I used the correct number of hours for the SOW tasks?

Items 1. and 2. are feasible with access to the right databases, but they have to be specific transaction-based rates rather than benchmark estimates. Item 3. is doable but requires a more sophisticated assessment of the requirements-to-skills match. We often see quite a bit of overspec’ing here, as there is typically no incentive for the vendor to supply the person who can do the job but isn’t overqualified. Linked-in searches of named resources can be quite illuminating here. Item 4. is clearly the hardest to do, but good estimates can be made by analyzing similar SOWs across different projects and buyers over time. We often find significant variances that simply cannot be explained. It is the very question of quantity that a vendor’s superior productivity technology should address. When comparing large SOWs both before and after changing the incentive structure, we have measured reductions of up to 50%. We have. Productivity is the name of the game and usually beats micro-management.

Longevity. Changes in market conditions are common and well-designed SOWs can handle them while preserving the relative competitiveness of the contract. If for example per diems for certain jobs rise, the buyer really has no advantage from having a great contract, as the resources will leave and be substituted by lower-skilled ones. Worse, when contract terms require adjustments due to changing market conditions, these in-flight renegotiations are almost always non-competitive, leading to an erosion of the relative competitiveness of the SOW.

It is worth investing time and effort in figuring out long-term pricing structures as they enable long-term vendor relationships, possibly at the MSA level, which would cover multiple SOWs. In reality, follow-on SOWs with incumbent vendors are not subjected to rigorous competition, leaving substantial value on the table. Buyers should avoid sourcing individual POs.

Incentive Alignment. We define this as the alignment of vendors’ and buyers’ interests in providing the maximum SOW ROI over an appropriate time horizon and with changing environmental conditions such as technology innovations, productivity, pricing, etc. It is without a doubt the most powerful lever available in the strategic sourcing arsenal but often poorly understood and underleveraged. As we will discuss later in this paper, the pricing approach is the key tool to ensure that the vendor works on the buyer’s behalf and that risks and rewards are properly shared. Different elements of the SOW require different pricing approaches and no single or simple pricing scheme will be sufficient.

Compliance. The SOW should measure and, to the extent possible self-enforce, non-price terms related to quality, deadlines, security, DEI, industry regulation, SLAs, and key operational performance metrics. Again, we find a lot of legal SOW language that deals with what happens when things go wrong, but few terms designed to prevent and correct for failure in performance.

Correct Pricing Approach is Key

In any contract, you get what you pay for, i.e. what you incentivize. SOW contracts are difficult because they usually do not represent a tangible and fungible end product that can be priced in a competitive market. However, the other extreme of managing all the inputs into the process (resources with labor rates, etc.) is typically doomed to fail because it is counter to the very reason why the buyer hired an outside vendor in the first place; their ability to enhance productivity beyond what the buyer could do by directly hiring resources. There isn’t a simple solution, but given the huge cost, risk, and importance of SOW projects, it is well worth spending the analytical effort as part of a strategic sourcing process to determine the best pricing and incentive structure.

Internal Cost and Pass-Throughs

The decision to hire a vendor for a project needs to always include a serious consideration of whether it makes sense to run the project internally, i.e. a classic make vs. buy analysis.

The typical frameworks that are being used for making these decisions consider whether the activity is core or non-core and whether the risk of outsourcing is high or low. Non-core, low-risk activities are then slated to go outside. The problem with that is the definitions of core and risk are usually subjective and not well developed in the decision-making process. The alternative framework below considers the maturity of the provider market, whether vendors are better at the task than you, and whether the capability is competitively differentiating. The resulting action recommendations are quite specific rather than a simple go/no-go.

Make or Buy Decision Framework

If the decision is made to use a vendor for the project, the internal costs of managing and more importantly the opportunity cost of NOT managing or under-managing the project must be considered explicitly. There is a wide body of knowledge about this subject so we will not elaborate further in this paper.

Pass-Through management can be important if the vendor bills the buyer for sub-contracted goods or services, i.e. when the vendor acts as a purchasing agent for the buyers. Clearly, the buyer should insist on at least the same or better purchasing processes and controls than exist internally.

Pricing Approaches Overview

There is no simple pricing approach that works in every case and most SOWs require a hybrid pricing approach. The framework below looks complex but has been proven to work over many years of consulting work. We have arranged the possible pricing approach from Task Pricing (useful outputs) to Portfolio Pricing (groups of tasks) to Milestone Pricing (progress metric) to Key Talent to Cost-Plus Pricing which we consider the last resort. Most SOWs will use several of these approaches for different elements of the project depending on the nature of the project.

Hybrid Pricing Framework

We recognize that despite our best efforts to create a detailed pricing schema there will always be an error term or behavioral x-factor that we cannot capture well. We suggest that this is handled top-down via smart budgeting whereby the parties agree to dynamic “not to exceed” amounts that protect the buyer and in a bottom-up fashion where overall project performance risks and rewards are shared with the vendor. These are overlays of the pricing approaches and should always be employed.

Task-Based Pricing

Being able to break down the project into identifiable tasks for which the buyer pays the vendor is obviously the gold standard and its usage should be maximized in any SOW. The challenge is to define tasks well enough so that any neutral party could clearly decide if it has been delivered or completed. Furthermore, such tasks should be able to stand on their own and have transferable value by themselves. In other words, if you switch vendors mid-project could these completed tasks be used without any incremental effort or cost impact?

Portfolio Pricing

Portfolio pricing is a variance management technique for tasks that exhibit natural deviation which is not driven by anything identifiable or predictable. Therefore, it requires a large number of tasks that are similar in their a priori known characteristics. A classic example is legal services for frequently occurring cases such as worker’s compensation, various insurance defense, or employment law. The incoming legal case looks standard and some end up being more difficult while others settle quickly for inherently unpredictable reasons. This average pricing approach also underlies all capitation risk pricing in health insurance, so there is a wide body of mathematical knowledge and management techniques available. Key considerations include careful portfolio construction (i.e., what to include in the average priced portfolio?) and explicit rules for managing extreme outcomes (e.g., when a legal case blows up) so that risk is not inappropriately transferred to vendors, which inevitably results in padded pricing.

Milestone Pricing

While similar to Task pricing, this approach is less desirable, because milestones are really hypothetical measures of progress. There is a difference between five tasks being completed and ten tasks being half done. We recommend this technique only when task pricing fails and when milestones can be objectively measured and view it as more of a management technique that identifies early warning signs.

Key Talent Provisions

In situations where the vendor choice is highly influenced by the vendor having impressive people, one must make sure these people actually work on the project. It may be worthwhile to agree to very high per diems for “superstars” and ensure they spend a defined minimum amount of time on the project. Superstars often come with their entourage, trying to transfer some of the exceptional talent to their team to get operational leverage, which should be avoided.

Cost-Plus

Finally, when all else fails, buyers try to re-engineer their vendor’s cost structure to make sure there is no excess. While common, we find this approach fundamentally flawed as it ignores all productivity differences, innovation, and technology. We see a lot of SOWs in our consulting work that are structured this way which allows us to perform interesting benchmarking exercises that give us a fact-based sense of the savings opportunity, as we discussed earlier in the paper under “Competitiveness”. However, we would advise against using this approach in sourcing or contracting, as there are much more powerful approaches available, which we will discuss in the next section.

How to Strategically Source SOWs

Strategically sourcing SOW projects requires that the buyer is willing to establish a strategic relationship with an appropriate set of preferred vendors for a significant portion of current and future projects. Sourcing only when an immediate need has arisen like PO sourcing is suboptimal since the buyer is in a rush, must buy a product or service and does not have the benefit of future volume leverage. While buyers often view every project as unique, that is clearly not the case because the same set of vendors typically supply such services. Often, buyers execute serial purchase order-level sourcing events, rather than making the strategic decision to call a timeout. While they pause during the process, buyers can aggregate multi-year demand with a smaller set of suppliers, which can increase the “value at play” by orders of magnitude.

Aggregating Purchasing Volumes

Prototyping and Baselining

While it might be hard to predict what future projects could look like, any buyer has close to perfect information about what happened in the past. Going back a few years and documenting in detail how prototypical projects have been executed can serve as the structural foundation for the baseline and the RFP evaluation. Each prototypical project, e.g. ERP implementation, engineering installations, litigation, helpdesk, training, etc. has a total cost, known resources who worked on it with detailed time records, locations, per diem rates, etc. If this data is hard to come by internally, a quick RFI with incumbent vendors who are highly motivated to participate in a future RFP process can solve the problem. This gives the buyer the ability to baseline at multiple levels of abstraction in accordance with the desired pricing approach. At a minimum, we suggest documenting the prototypes in Cost-Plus, Task, and Milestone versions.

These prototype projects are then matched with a financial baseline, derived from A/P data for recent time periods to establish a formal baseline against which results are to be measured and to form the basis of decision-making.

The baseline should reflect future demand and requirements while also being grounded in historical reality. One cannot idealize the baseline by assuming that the future will be perfect, when past projects have been far from flawless. As the baseline is disaggregated into its price, quantity, and specification components, we can and should adjust it based on any labor rate changes that may have occurred in the past.

RFP Design

We will focus here only on the design of economic terms and ignore the legal dimension. The objective here is to maximize competition, make bids comparable, reduce or eliminate any vendor risk premium that may arise out of unclear specifications or inappropriate risk transfer, and most importantly, incentivize the vendors to maximize project ROIs. We usually bid out each prototype at three levels:

1. Top-Down: All-in price for each project prototype

2. Mid-tier: Task, milestone, or portfolio pricing based on intermediate products

3. Bottom-up: Cost-Plus with rates, job descriptions, hours, etc.

Vendors should also be informed that there will be big winners and big losers as the buyer seeks to consolidate its vendor set and aims to lengthen the term of the contractual relationships. Buyers should maximize the “value at play”, by making it clear that this is not business as usual and therefore worth the vendor’s effort to participate in the process. There should be explicit and detailed risk and reward-sharing mechanisms, as well as an outline of how specific purchase orders will be allocated to a vendor within a small set of preferred vendors. We typically recommend that the buyer commits to market share ranges for winning vendors, with the contractual rates representing ceiling prices that may be underbid for a specific purchase, resulting in increased market share within the agreed upon range. The illustration below shows a dual vendor set-up with declining cost over time due to productivity advances.

Maintaining Ongoing Competition

RFP Process

Once the RFP is designed, executing the process is fairly straightforward, if tedious. The buyer issues various documents (Intent to bid, NDA, RFI, RFP) to a set of vendors that the buyer could work with. It is important to keep an open mind at this stage and not eliminate too many suppliers before their proposals can be assessed. Depending on the software used to run the RFP, there may be quite a bit of manual data manipulation work, since most eRFX platforms only support catalog or SKU-style pricing approaches and cannot tie bids back to baselines.

It is paramount that incumbents do not have an informational advantage in terms of implicit specifications (how things really work at the particular client). We recommend that buyers provide detailed information about the demand profile, but disguise prototypes sufficiently so that the incumbent cannot recognize it as an actual past project.

Hybrid Pricing Capable e-RFP Platform

Analysis and Negotiation

The purpose of this stage is to determine an optimal target end state with a feasible set of bidders and terms based on fully negotiated bids.

We will not go into the important but mundane process of ensuring data integrity for both the baseline and the bids, except to note that there appears to be an inverse correlation between the quality of a buyer’s data and savings opportunity: Poor data or data availability usually means high potential savings.

Because the baseline and the bids exist at multiple levels of abstraction or disaggregation and are available from multiple bidders, there are many degrees of freedom to analyze the data in terms of “synthetic minima”. Simply put, one could compare bidder A’s price for prototype X to bidder B’s for the same, but one can also take all the minima of the task-based bids and construct a synthetic bid that no single vendor submitted. By doing this analysis at different levels, significant insights into differential vendor economics and pricing strategies can be gleaned, which is highly useful for negotiations. We fully recognize that this analysis can be quite complex, but strategic sourcing analysis is usually about uncovering many small improvements that add up to meaningful savings, blocking and tackling, tedious iteration, and outworking the suppliers, instead of big, brilliant insights. Simplification of pricing approaches only to facilitate easier analysis is neither necessary nor acceptable.

Negotiation is really an iterative process of leveraging the fact that the buyer is now in possession of more information than any supplier. Sometimes the bids are so confused that a guiding hand is needed, so the sourcing team establishes a target rate card, i.e. the parameters of a prototype cost model that is internally consistent, and then asks vendors to agree to that. It is critical that all bidders remain convinced that they can either gain a lot or lose a lot of business and that there really is no preference for incumbents outside of cold, hard economics, and math. In most cases, incumbent suppliers cave at the last moment and match the new suppliers’ terms.

The decision to prefer an incumbent should be grounded in logic and fact, not just convenience or politics. Switching is a lot of work for the organization and thus not popular, when in fact it might be the right and long overdue decision to make. We find it useful to challenge estimated, huge switching cost assumptions by equating them to FTE costs. When procurement says it costs $1M to switch a vendor and suggests it is not worth it, they are really saying that ten people working on it for a year couldn’t figure it out.

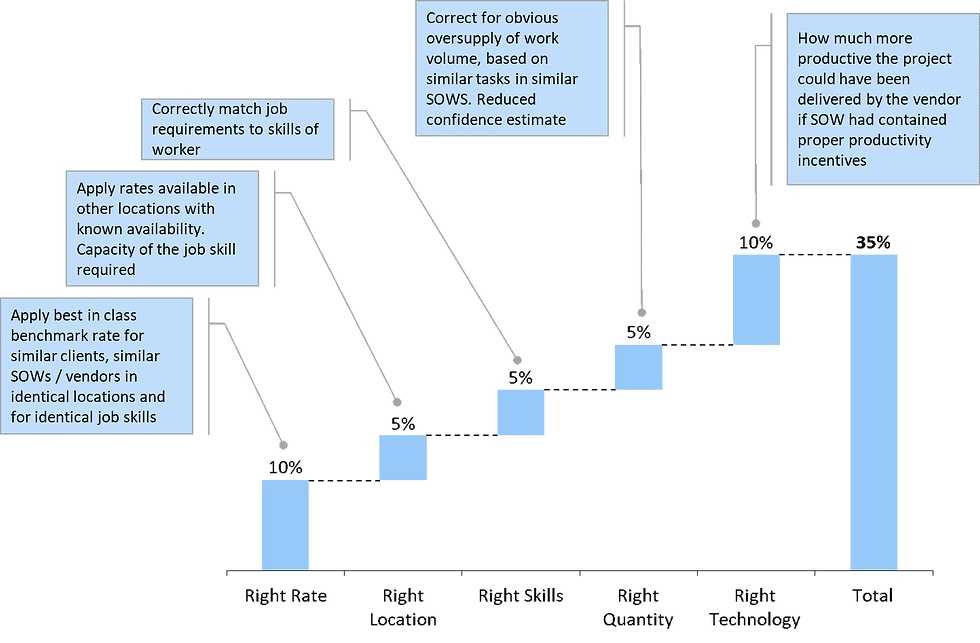

Performance Improvement Potential

The results of the described process can be quite dramatic. We frequently see savings of up to 35% with the majority coming from applying appropriate labor rates and incentivizing vendors to be as productive as possible. While the process of establishing best-in-class SOWs is analytically challenging, there is really no alternative, given the increasingly strategic business transformation functions being performed by outside vendors.

Performance Improvement by Source

% of Baseline Cost

For more information:

Contact the author at hans.dau@mmgmc.com

+1 310 909 7600

Comments